About REW (Immémorial #6) : « What is surfacing and submerging » By Pascale Weber

(Scene, C. White; A. Oddey. Scene , ed. Intellect, pp. 99-116, 2013, 2044-3714, hal-03849602v1)

Immémorial is an artistic project that calls upon computer technology, immersion, video image and sound spatialization, and finally interaction; the technical supports used for these works act as a metaphor, a mirror for our cognitive memory, our imaginative processes. This work of art was developed with the collaboration of scientists and specialists in cognitive physiology and psychology.

For the viewer it has evolved into an experience of (re)constitution which hints at a taxonomy of models of constituent memories forming our identity. The discovery of our senses, our earliest emotions, our frustrations and our desire is treated as evidence through reconstituting them like a nature study: analyzed, identified, and quantified… a typology of the shared places of our memory, defining their « natural » or « cultural » characteristics, their continuation by fiction.

As often happens in immersive mechanisms, the different versions of Immemorial intend to pull the spectator out of a reality too complex to grasp and invite him, evoking the real, to focus on a detail, a micro feature. This is the world narrowed in a limited and controlled space, a metaphor for an actual societal issue: can we finally see the world as a plurality? Can we think outside of our bodies, from other bodies, from a common body? Can we escape the limits of our physical bodies into this common body, as a network, extended by the computer, the mechanism in progress…

Immémorial has been declined in six successive multimedia mechanisms. The last one, called Rew, is currently nearing completion. The different versions invite the spectator into the heart of mechanism with a more and more complex system of unpredictable and/or interactive treatment of part of the data. Each of the versions deals with reminiscence and the interrelations in our brain between our cognitive functions of identity and memory.

In the multimedia project Immémorial, undertaken in 1995, we find sequences of animated images (photos, 8mm film, video…), which have been reorganized, re-edited,and re-filmed many times; and sound sequences (audio textures, instrumental, interviews, voice-overs…) reworked as well, during workshops in studios of sound creation (Euphonia, GMEM, Marseille).

The entirety of the sensory elements are organized in databases and directories. It constitutes a collection, a wide range of audio-visual case-studies, that establishes the sensory conditions that result in the viewer experiencing resurfacing memories, and above all that help us to understand how our thoughts follow and summon each other.

1- Project background :

Memories are superimposed and are reactivated randomly: often without respect for chronology, nor understanding why this memory evokes that one, sometimes without evident coherence with the context. But how does the time of memory work?

The first two versions of Immémorial evoke the texture of the memory, as an accumulation of recordings, perceptions and points of views. I intend to elaborate a cognitive fiction by proposing a fictional access to all my video films and the sounds I’ve recorded. The compilation contains saturated data, multiscreen-composed with repeated overlapping, randomly crossed like a Dada cadavre exquis. I have conceived the earliest versions in this way, by adding and successively inserting iconic, textual, graphic and sound elements, which express emotional, perceptive and spacial sensations.

The first version, a compilation within a 21/2hour film that was structured in 4 parts constituted of short audio-visual video clips (1996-2005) was presented in Nice, in 2006 (MAMAC). I proposed a continuing assembly and editing which obeys narrative progression and beginning-to-end chronology; Dark banks (childhood), Time of machines (entering into adulthood), Domestic pains (founding a family), Forgetting (old age).

The second version, modelized in 3D with Owen Kevin Appadoo, presents 4 audio-video projections (2005-2006) still following linear time, but simultaneously projected. This version forced me to re-edit the set of video rushes, and raw files and compelled me to devise a way to spatialize the image on 4 screens, and the sound, with many micro-speakers “zoning” the audio material and physically involving the mobile viewer.

From the third version onward, in a still very intuitive conception, Immémorial became a more realistic metaphoric representation of the memorial process. Both poetic and using cognitive illusion, Immémorial simulates the functioning of episodic memory. Different specialists in cognitive sciences have confirmed what I had intuitively guessed. The truth of the memory is not content-related but can be found in the manner of reorganizing, assembling the elements: an interactive story composed of “narrative segments”. The spectator has to assemble these “signs”. He perceives and interprets them differently depending on their order. Sequences can be cut short or stopped if the spectator chooses to: our memory is not a “hard disk”, but a dynamic function, a meaningful network. Like language, memory is a dynamic system of relations.

Immémorial progresses then as an instinctive, poetic and perceptive-sensorial proposition which deals with the encoding mechanisms of our memories, and which highlights the relationship between testimony, imaginary fiction, and autobiographic narrative. The project, then, elaborates a kind of “ authentictional ” narrative. With this mechanism, I wanted to reveal the infinite potential of associations and emotional junctions. I thus continued to amass images, sounds, and testimonies in order to compare the images of the first versions with anenlarged corpus, which helps nevertheless to bring to the foreground objects which evoke my own experience of memory.

The interactive installation of the third version of Immémorial is executed on 4 screens. Two pairs of pre-associated sequences are simultaneously displayed on the screens, whereas only one soundtrack is randomly broadcast. By choosing words on the interface-screen, the spectator activates the association of pairs of modules. Words are associated to movies: by choosing words I defined the first databases. It obliged me to organize the segmentation and the recompilation of the audio and visual data. Words appear on the screen inlaid in the image, having randomly been chosen in files containing lists of words. The spectator can write his own words, which will then be inlayed within the image, directly throughout the interface. The words come back randomly at irregular and longer and longer intervals, as reminding thoughts, like memory tracks of the previous sequences. This third version of Immémorial was created and presented for the conference “About virtual space and body in presence” (University of Auvergne, Le Puy-en-Velay, 2009).

The fourth version presents for the first time the double simultaneous display of the film (in full screen, 25 images per second on the same surface and using the persistence of vision; and the inset display of the same images overlapping throughout the background, a succession of labels, drawing a “tunnel of images”)(2008). In this version, presented again in Nice (MAMAC, 2010), I tried to make perceptible the narrative temporality of a sequence and the construction of duration One can manipulate, accelerate, rewind or fast forward , by establishing a formal relationship between the duration of the movie and the space of the screen: the “tunnel of images” makes visible the progression of time in the process of making a video film and the phenomenon of visual continuum(the persistence of vision?) . I wanted the spectator to be able to enter into the duration of the film and to be faced with the duality of the narrative time and the time of the audio-visual object. The permanent moving overlapping of labels cancels the unique point of view, sketching out a line of views with many convolutions. The film duration is no longer an absolute, but just a relative input: Each observer considers it, according to his position in space whether at rest (standing or sitting) or in motion.

The fifth version was presented several times, with some variants during the residencies in Marseille (2011):

-use of a camera embarked for projection of mise en abyme of the image (a formal technique in which an image contains a smaller copy of itself, the sequence appearing to recede infinitely), of the mobile point of view of a spectator (the Cité de la Musique de Marseille, installation created with Jean Delsaux, Marseille, 2011),

-sound spatializing with adaptation to the volume and to the architecture of the room (workshop in the GMEM, 2011),

-a blend of images and their 3D models (MAMAC, Nice, 2011),

-lastly certain memorial clips were punctually shown (Vidéoformes festival of Clermont-Ferrand, 2011)…

Two major accomplishments in this version: firstly the sound spatialization and the constitution of banks of sound textures, secondly the sound recording of voice-overs of a narrative. These voice-overs determine many visual and audio elements of the video clip, defining a universe, an atmosphere, a mood, a typology of recollections. I’m obliged to consider the relationship between the image, the sound material, and the voice-over (subtitled). I refused this time to saturate the senses of the spectator, I preferred to insert fadings of the sound and the image, in order to rhythm the demand of the senses of the spectator and to leave « empty » and silent moments, available spaces in imagination. Effectively, in the fifth version, I understood that our emotional, perceptive body really welcomes the technological resources only on the condition of being, at least partially, an actor of the mechanism. The meaning of being an actor in a multimedia work of art remains to be defined.

Each version is a calculated system, every sensorial element has been defined in advance, all the possibilities have been programmed by laws randomness and probability, by the computer. By pushing the buttons, which activate video sequences and control the inset display of the images and the navigation through files, the spectator interacts with the mechanism. But it works also in by withholding; it is in the silences I deliberately introduced, the blanks and the interruptions, the incoherence and the black screen that the visitor reconstructs the gaps of information and participles of the audivisual artwork.

Examples of recorded sound testimonies (voice-overs and subtitles):

From The Teddy bear.

“When I got him, I was just a little kid, maybe even a baby. His name was Wawa.”

“He must have ended up in some barn, having moved from house to house, and I kept him.”

“… That’s where the ear got torn off, by a friend. I held on to the ear until the end of the stay, and my mom sewed it back on. The only memory I have of this toy is just that: the time where my friend ripped his ear off.“

“I don’t think we can really see ourselves as children. In my case anyway, I can’t see myself as a child. I have images, but every time I have gone back to a place associated with those images, I’ve been struck by the dimensions of everything.”

“… The only thing that that evokes for me is the end of Citizen Kane. And I think the only reason that I just can’t get rid of this teddy-bear is because there is an enigma, something that formed me that I no longer remember.”

From Chilhood Vibrations.

“Sound to me, in my childhood, was always associated with certain situations.”

“I was really quite young, four or five, I would climb up on a wooden dresser, sit down, and vocalize. What was essential to me was producing a vibration. I set myself into a state of vibration with the dresser.”

“It was an agreement, an accord with the dresser, a vocalization ‘Ah Mmmmmm’, a continuous sound something like that, that I sustained. A middle pitch, not even very low… that’s how I can be sure that it was even a sound. In any case, it was a vibration.”

“It might be that music is more than just sound, you know. In my memory, it is something approaching mystical.”

Owing to the technical process of spatialization via eight points and sound trajectories, and the four-sided presentation of the images, Immémorial projects the viewer, in the fifth and the sixth versions, into the heart of an environment which is divided into 27 ambiances based on strong experiences, in order to awaken long-term memory. So, on one hand Immémorial deals with the functioning dynamics of our memory and its anticipatory prolongation through our imagination and the network of meaning that these functions continuously weave. One the other hand, the structure of the computer language used for distributing the video image and sound spatialization guides the construction of the narrative and the return of the memorial experience in the device.

2- Presentation of REW, version #6 of Immémorial:

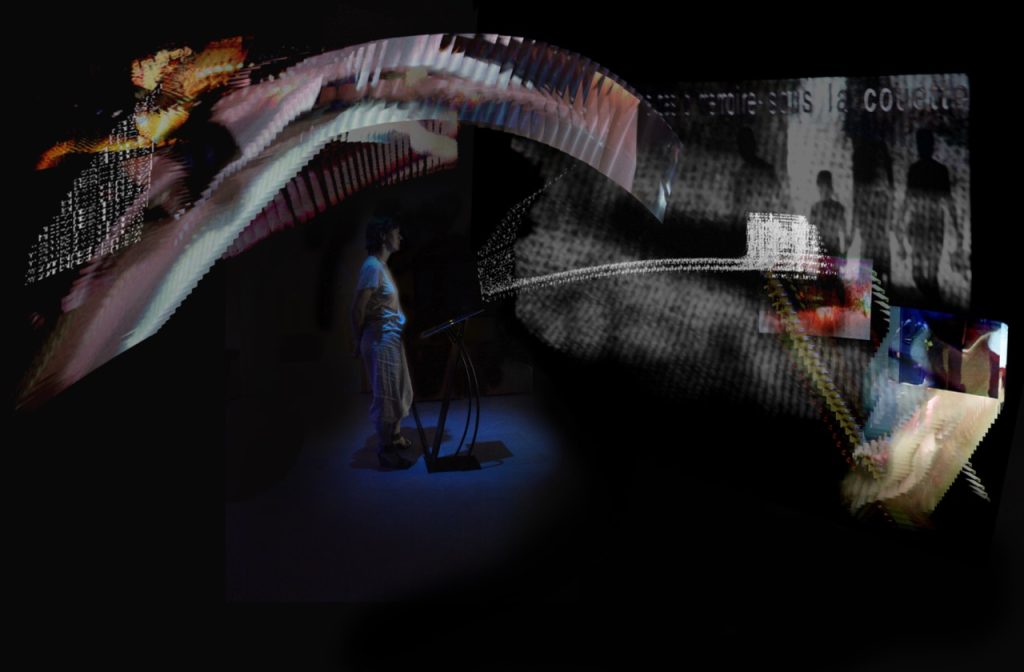

Rew is the abbreviation of Rewind. This term evokes the practice of audio and visual recordings. It insists on the effective manipulation of the duration and of the structure of an event by editing. It demonstrates the permanent rewriting of history by revisiting the past. In this version, I hoped that the spectator would feel that he is traversing the space, but would equally feel traversed,probed by the mechanism. For this I imagined a place without landmarks, without verticality nor horizontality, without walls and without specific formal structure.

The box, the cyclo (cyc/ or cyclorama) and the cube are spaces constructed for the machine, standards and models of the linear perspective. The space which is delineated by our field of vision is very different, as is the space covered by my arms which stir around me by drawing circles, and also the space designated by the sounds reaching me, from the front or behind, from the ground or the sky. All these volumes are without edges and without faces. It is this space which I wish to reconstruct in the sixth version entitled Rew: an enclosed volume for a non-systematically centered spectator, an irregular envelope, a little bit vague with imperceptible edges. A place which reminds the spectator that in « real » life, the limits of his field of vision have nothing to do with closed architecture. Our experience of vision is much less taxing than in an immersive Cave.

Up to fifteen persons can enter in the place delimited by a delicate canvas structure, which is also a screen for video-projections. Eight speakers surround the place. Two video-projectors light up inside the structure. Both of the projectors show a specific viewing, and run the pictures of the same film: traditionally on a large screen, playing with the illusion of movement, or inside little frames drawing the same kind of tunnel of images as the versions #4 and #5 on the screen during the running. The technical equipment is outside of the room. In the center of the empty room tiltable chairs allow spectators to look at the pictures projected on the covered-canvas and to listen to the different spatialized sounds. There is also a control desk with three luminous buttons which enable the spectator to interact with the playing of the film.

The Interactivity is ordered by the three buttons of the control desk. When the spectator presses:

The left button:

The film running 25 images per second on the full size screen is modified and replaced by a succession of screen-shots, compiled on the audio rhythm, with fading transition between the images. One just has to press the button again to make the film run ”normally” with 25 images per second.

The middle button:

When pressing this button, one stops the running video clip. A grid of frames of the different video clips is displayed on the screen, giving a global look at the data. Randomly chosen in the 27 audio-visual moods database, a video clip appears on the full screen. Simultaneously a kind of tunnel of images plays on the canvas structure: it is the viewing image per image of the same video clip, which appears in little frames (projected by the other projector).

The right button:

The tunnel of images is drawn by the running image per image of the video clip, each time in a different little frame which is projected farther along the trajectory, so that it seems to progress on the surface of the screen. A maximum of 200 frames (25/second) are displayed on the screen, the first fade as the new ones appear. When the spectator presses the button, instead of a tunnel made of 25 frames per second, only one frame per second is displayed. This frame stays on the screen up to a maximum of 200 frames. Pressing the button again, causes the tunnel to run at 25 frames per second once again.

The interactivity is subjected to arbitrary power (what is defined in the device and on which the spectator can have no possible effect) and to random process (in which the spectator can intervene only by suspending the results and by activating a new unpredictable combination):

As in the fifth version of Immémorial, the audio recordings are both organized in an arbitrary and random way.

– Voice-overs, bound to the narrative, are broadcast in stereo. They always happen at the same key-moments of the video track, so they are synchronous with the English subtitles.

Just as the spectator hears a voice, the image disappears and the spatialized sound is suspended.

– The sound material, listed by databases, bound to the video clips is edited in real time by random composition of various sounds, audio treatments, behaviors and trajectories and the technical process of spatialization via eight points of this improvised sound-track. Every video sequence is linked to 6 sounds: there are 3 specific sounds per film, and 3 associated sounds—sounds specific to one of the other 27 films. Each of these sounds is emitted in 3 particular modalities of spatial transmission (trajectories). So, every movie possesses an appropriate audio base which is randomly calculated and played at every reading.

3- The place of the experiment:

Our Memory changes because our relation to reality is also unstable. Like the continuous movement of the bright, colored, sound data, memories appear within the framework of a context, an association of events. The global treatment of the project by audio, video and trajectory directories allows me to highlight the explosion of our perceptive experience and the construction of our identities. Immémorial expresses a multiplicity of the Self, the intermixing of the narrator’s, the characters’ and the creator’s identities. The immersion,however, allows me (or us) to define and to experiment with a perceptive context, to manipulate the senses and to control the sound, visible, spatial clues for the visitors, to delete the points of reference outside, the natural light, the noise of the street… The immersive spaces of the different versions of Immemorial is a laboratory that immerses visitors’ bodies in a kind of daydream by a random succession of different memorial moods. The mechanism is immersive at different levels: voice-overs, audio, visual and spatial. The time of immersion is that of the happening, subject to the organized protocol: patches have no memory, they have no backgrounds. Events are not attached to a timeline. Activating them, I trigger videos, sounds, text insertions each time in random succession.

Movements within the setup are multiple: within the images (fixed, animations, video clips: slow or fast action, filmed spontaneously or with a scenario), the path along which frames follow one another in succession, or the projections that the viewer can interact with, the sound trajectories, the sub-titles and voice overs alternating with image and sound, the pronouncing of words (saying a word, a phrase, a secret, an anecdote, announcing, telling, describing, thinking out loud), and the viewers’ own movement. Each element continues at its own speed. None of these fluxes are continuous; the global mechanism shows a succession of chaotic perceptive-sensory elements. The viewers let themselves be carried along in the moving space. The movement of the audiovisual elements, the overall dynamic feeling of the setup, and the loss of points of reference quickly entice the visitors to sit down and observe from a fixed point of view: the mobility of the image and the spatialization of the sound tranquilizes viewers in fascination, stilling rather than exciting the body. Bodies present, near other bodies, all together without really seeing each other, but knowing they are together, witnessing together the intimacies of the people whose voices they hear in the voice-over. In this way, the isolation of the immersive experience actually accentuates the feeling of shared experience.

At the same time, the presence of viewers fluctuates, and they are permanently adjusting. Immerged and submerged, they are present, being immerged in the mechanism which speaks of memory, projecting them back into their oldest memories; they are absent, too, distanced from the present by their imagination and the memorial journey before coming back to the present and their presence in the immerged surroundings.

Conclusion:

Though it is rarely the case in the present conception of immersive setups, an immersive device allows us to do without the principle of viewpoint and to escape the need for a coherent, global structure which is subject to that viewpoint.

The space in Rew is continuously activated—bodies activate and reactivate the space, becoming themselves active, projecting themselves into the action either by imagination, memory, or anticipation. Sound and visual matter abound. The immersive apparatus allows visitors to absorb a kind of moving energy, to feel a possible harmony between one’s body and the environment inside this synesthetic workshop-laboratory: the feel of one’s breath, the beating of one’s heart, the visual and sound perception. The work of art allows each individual to represent himself mentally, to imagine himself in a world where he no longer knows his place.

Rew is the polar opposite of an immersive video game. The space isn’t an action-reaction zone, but that of a necessary and temporary abandon of the body, a letting go, a sensory-perceptive experience of the presence. In this way, the the immersive mechanism is entirely capable of causing memories and emotions to surface. But more to the point, the immersivity allows us to experience the instability of the world, as a reality which comes to us, endure, over which we have no control.

Rew doesn’t conform to the laws of perspective. I didn’t burden myself trying with creating an image that represented a tangible reality. Rew is not seeking to recreate the most realistic depth of space possible. And yet I think that the setup is akin to the Renaissance usage of perspective because it’s goal is to create an illusion: striving to create a cognitive fiction (here a perceptive-sensory journey) through a common memory. It is a fiction which calls upon the entire body, but instead of the illusion of an image which we take to be a bit of the real world, we are presented with the illusion of experiencing an authentic memory. Our own experience, anticipated or imagined, is revivified by the solicitation of our senses, by an illusion of immersion in another time and place, by an interior experience, a fiction of identification.

In order to travel in time, we need to imagine places where we have spent time (or could spend time), where our unrestrained body has felt desire, frustration, and its own limits: the body must be involved in the space in order for memory to become activated. Rew offers a reconstruction of the imaginary space, a past which offers us a physical access to the present. This reconstruction may fall into the category of illusionist works, whether concerning simulation, stimulation or optical illusion; it functions however, as a contemplation of our identity.

Immémorial is coproduced by the GMEM (Residences 2010-2012), the SCAM (Pierre Schaeffer Prize awarded), the LEEE (Laboratory of Aesthetics and Experiment of the Space, University of Auvergne), the CERAP (Research Art Center of the University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne) and Euphonia (sound design Studio, Friche de la belle de mai, Marseille).

Immémorial is written, conceived and created by Pascale Weber; audio engineers: Charles Bascou at GMEM and Lucien Bertolina at Euphonia; multimedia engineer: Luccio Stiz; multimedia interactivity technician: Sylvain Delbard; 3D support: Owen Kevin Appadoo; technical support, conception of the setup: Jean Delsaux.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

SOUCHEYRE, Gabriel, “Portrait of an artist: Pascale Weber”, in the Web magazine Turbulences Vidéo #65, October 2009.

http://www.videoformes-fest.com/portraits-d-artistes/pascale-weber/ (accessed in 18/10/2011).

SOBIESZCZANSKI, Marcin, “A Walk through Pascale Weber’s Immemorial”, in Turbulences Vidéo#65,

DELSAUX, Jean, “Immemorial: Experiments in Forgetting”, in Turbulences Vidéo #65,

TUFANO, Antonella, “About Immémorial”, in Turbulences Vidéo #65,

WEBER, Pascale (2003) – Bodies tested in projection mechanism (Le corps à l’épreuve de l’installation-projection), Paris, FRANCE, ed. L’Harmattan, ISBN: 2-7475-4609-8, 252 pp.

WEBER, Pascale, “Resistance and others properties of the artistic material“: LACHAUD, Jean-Marc, LUSSAC, Olivier, supervised by, Arts and new Technologies, (Arts et nouvelles technologies), ed. L’Harmattan, 2007, 65-76, ISBN: 978-2-296-03160-9

WEBER, Pascale, “Vague spaces and Interconnections”: WEBER, Pascale, DELSAUX, Jean, supervised by, Virtual Space, Body in presence, (De l’espace virtuel, du corps en presence), PUN ed. (“Epistemology of the body” collection), 2010, 7-33 & 216-218, ISBN: 978-2-8143-0009-5

WEBER, Pascale, “Superimposing and inlaying Aesthetic : For overloading and thickening the image “: SOBIESZCZANSKI, Marcin, MASONI LACROIX Céline, supervised by, From the split-screen to the multiscreen- Spatially distributed video-cinematic narration, Bern, Peter Lang International ed., 2011, 162-182, ISBN: 978-3-0343-0325-5

WEBER, Pascale, “Immémorial (1996 – 2011) An immersive memory mechanism“, in Avanca-Cinema, International conference, 2011, N°ISBN to come.